Networked Economy

ICT Employment Opportunities | B2C Electronic Commerce | B2B Electronic Commerce | E-Government

With only 50,660 sq km of landmass there are approximately 2 million people in the labor force from the 4 million in Costa Rica with an approximate 5.2% unemployment rate (CIA). In addition, 63.9% of the population is within the 15-64 age bracket (CIA), with the population density estimated at 78.4 inhabitants per square kilometer (Monge & Cespedes 5). By 2001, the GDP was estimated at $31.9 Billion (GDP-per capita: $8,500) (CIA) and the GNP-per capita was estimated at $4,009 (Monge & Cespedes 5). Additionally, Costa Rica ranked 41st in the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a good position to be at internationally (Monge & Cespedes 5).

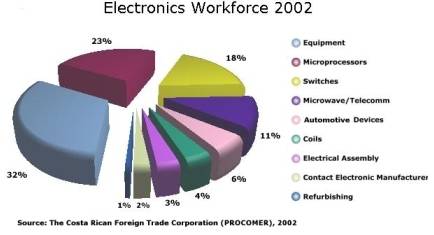

Costa

Rica’s three strongest forms of industry are tourism, agriculture, and

electronics (CIA). The 2002

workforce distribution in electronics incorporates many different industries

throughout Costa Rica, as seen in the ‘Electronics Workforce 2002 figure’

according to the CINDE (Costa Rican Investment Board). This has become a strong focus of Costa

Rica within the last decade as the information age has brought a new beginning

to the economy through offshore outsourcing to Costa Rica. Several factors are playing a role in

this trend. For example, the

average annual income of a Costa Rican in 2002 was $3,960 (BBC News), which

shows that the overall cost of labor is much cheaper in Costa Rica, even if you

add in the additional costs associated with labor. In addition, Costa Rica’s time zone matches up nicely with

the Midwest’s time zone (Isbister International, Inc.), which allows for U.S. companies to work

and communicate on a traditional workday schedule. If not for these reasons, the trend of offshore outsourcing

to Costa Rica would not be as prevalent as it is today.

Costa

Rica’s three strongest forms of industry are tourism, agriculture, and

electronics (CIA). The 2002

workforce distribution in electronics incorporates many different industries

throughout Costa Rica, as seen in the ‘Electronics Workforce 2002 figure’

according to the CINDE (Costa Rican Investment Board). This has become a strong focus of Costa

Rica within the last decade as the information age has brought a new beginning

to the economy through offshore outsourcing to Costa Rica. Several factors are playing a role in

this trend. For example, the

average annual income of a Costa Rican in 2002 was $3,960 (BBC News), which

shows that the overall cost of labor is much cheaper in Costa Rica, even if you

add in the additional costs associated with labor. In addition, Costa Rica’s time zone matches up nicely with

the Midwest’s time zone (Isbister International, Inc.), which allows for U.S. companies to work

and communicate on a traditional workday schedule. If not for these reasons, the trend of offshore outsourcing

to Costa Rica would not be as prevalent as it is today.

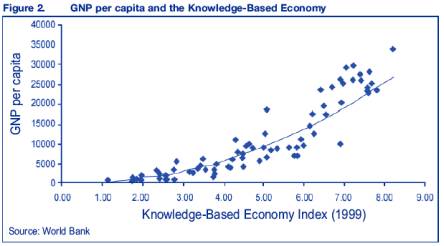

The IT’s role within the economy is important

as seen in the below figure—GNP per capita and the Knowledge-Based Economy (Monge

& Cespedes 12). You will see that as the

Knowledge-Based Economy  Index increased, the GNP per capita has

increased dramatically. This type

of orientation for the country will have positive effects on decreasing poverty

rates and increasing the services offered by Costa Rica. “Technology is like education—it allows

people to rise out of poverty by themselves. As such, technology is a tool for growth and development and

not just a price of the latter” (Monge & Cespedes 12).

This quote points out that without technology, Costa Rica may be in a

different situation as represented by neighbors of Costa Rica who have not

leveraged technology to their advantage at this point. Though, with the rate of inflation of

12.1% in 2002, workers will need to make more money in order to afford the same

life style they currently experience (CIA). By continuing to

leverage technology, the Costa Rican government and businesses will experience

fantastic future growth of the country.

Index increased, the GNP per capita has

increased dramatically. This type

of orientation for the country will have positive effects on decreasing poverty

rates and increasing the services offered by Costa Rica. “Technology is like education—it allows

people to rise out of poverty by themselves. As such, technology is a tool for growth and development and

not just a price of the latter” (Monge & Cespedes 12).

This quote points out that without technology, Costa Rica may be in a

different situation as represented by neighbors of Costa Rica who have not

leveraged technology to their advantage at this point. Though, with the rate of inflation of

12.1% in 2002, workers will need to make more money in order to afford the same

life style they currently experience (CIA). By continuing to

leverage technology, the Costa Rican government and businesses will experience

fantastic future growth of the country.

In addition to the Digital Agenda that Costa

Rica began, it was the first Latin American country to provide Internet

services. Therefore, showing their

dedication to leveraging technology.

The Digital Agenda is what the Costa Rican program is called in

order to modernize telecommunication infrastructures, provide universal

Internet access (Communication without Boarder Program), provide a centralized

Digital Government, digital business promotion (includes: finance for

education, on-line resources for tourism, and  the e-readiness program from CAATAC), and

governmental reforms for laws and regulatory issues that deal with privacy,

digital signatures, and intellectual property (Monge & Cespedes 14).

This program is still in the early stages of implementation.

the e-readiness program from CAATAC), and

governmental reforms for laws and regulatory issues that deal with privacy,

digital signatures, and intellectual property (Monge & Cespedes 14).

This program is still in the early stages of implementation.

Using the Framework,

Networked Economy would be categorized overall in Stage 3. Employment Opportunities and

E-Government are more solid within Stage 3 but B2C and B2B Electronic Commerce

are bordering Stage 2 and 3. The

population, as a whole, has to embrace the Internet within the home in order to

make E-Commerce transactions popular and common. Even though the individual categories vary a bit, businesses

and people have an overall lack of commitment (Internet in the home) to its

domestic advancement, through E-Government and E-Commerce, versus the

advancement of offshore outsourcing companies.

ICT Employment Opportunities

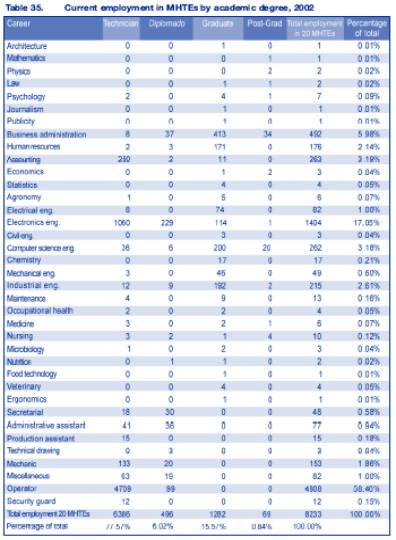

The results of a recent study (seen in Table 35) show that “MHTEs in Costa Rica employ relatively high percentages of people in categories such as laborers (58%) and electronics (17%)…[and lesser amounts in] business administration (6%), accounting (3.2%), computing and computer engineering (3.2%), industrial engineering (2.6%), human resources (2.1%), mechanics (1.9%), and electrical engineering (1%)” (Monge & Cespedes 103). Overall, there are an adequate number of workers available in all different trade skills to not only meet the current demands of employers, but also meet the future demands of employers and companies that may invest or open additional offices in Costa Rica (Monge & Cespedes 119).

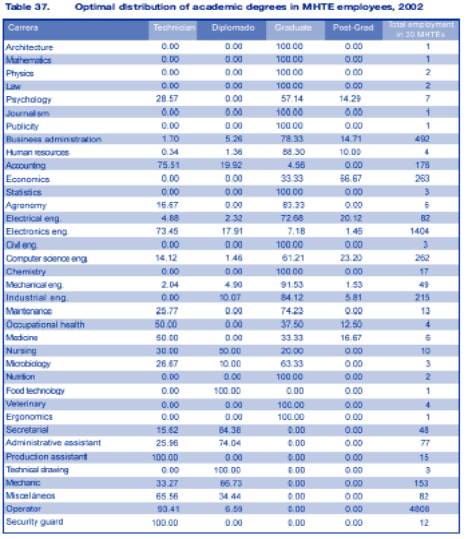

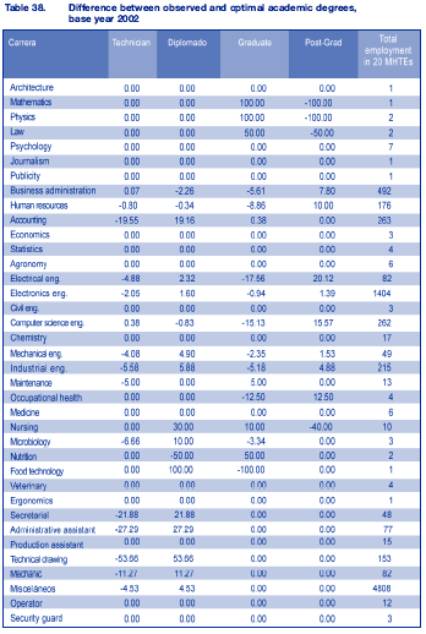

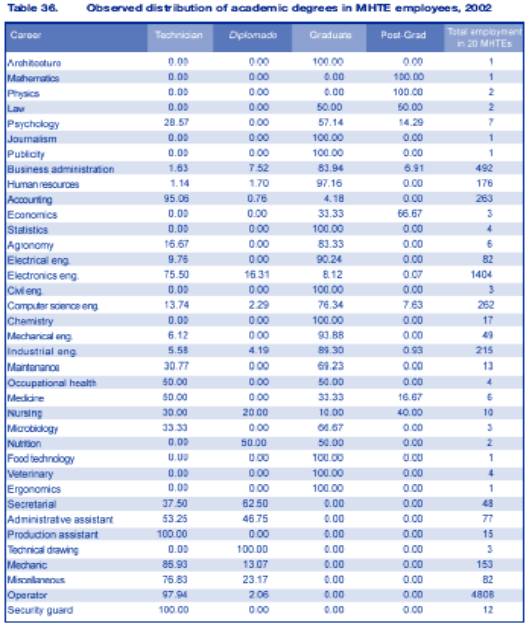

At the same time, the education levels that employers desire (seen on Table 37) for their employees are not being fully met. For example, current levels (seen on Table 36) of Computer Science Engineering technician are at 13.74 and the optimal level is 14.12, which is a 0.38 difference (seen on Table 38). These expectation deficits that employers are experiencing do not seem dramatic enough to cause any issues with attracting overseas business (Monge & Cespedes 118). Small adjustments to the supply of the different levels of education will need to be made for long-term stability (Monge & Cespedes 119). In addition to educational demands, other desired skills include problem solving, human

resource (people skills), computer programming, training and teaching, scientific and mathematical, financial administration, information management, foreign languages, and business administration. Overall, the attraction of plentiful skilled workers to companies that offshore outsource, make Costa Rica an ideal place to invest into.

B2C Electronic Commerce

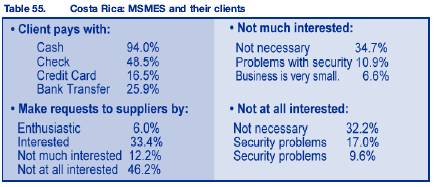

Only about 5% of the small and medium

businesses have a website, of which only 9.2% actively use the website to

collect payments (Monge & Cespedes 188). Most businesses do not

see the Internet as an advantage because the majority of Costa Rican’s only pay

with cash (94%) or check (48.5%) when purchasing items, as seen in Table 55 (Monge

&  Cespedes

195). Additionally, less than 5% of the Costa Rican households

have Internet access (Monge & Cespedes 196). Consequently, “less than

half of…[the small and medium businesses] are interested in carrying out sales

over the Internet in the near future” (Monge & Cespedes 195) because

the demand is not high enough for the investment. Furthermore, some

businesses do not see it as a needed aspect of their business because they

consider themselves small or they are concerned with security (Monge

& Cespedes 195).

Cespedes

195). Additionally, less than 5% of the Costa Rican households

have Internet access (Monge & Cespedes 196). Consequently, “less than

half of…[the small and medium businesses] are interested in carrying out sales

over the Internet in the near future” (Monge & Cespedes 195) because

the demand is not high enough for the investment. Furthermore, some

businesses do not see it as a needed aspect of their business because they

consider themselves small or they are concerned with security (Monge

& Cespedes 195).

Though, it is worth mentioning that 73.6% of

the consumers that use the Internet do so to comparison shop and 89.8% use it

for email (Monge & Cespedes 187). Therefore, you can count

a percentage of the sales as a result of information located on the Internet or

received through email even though there was no electronic transaction. By strategically placing key

information on the Internet, businesses can increase their customer base.

Electronic commerce is not very prevalent in

Costa Rica because of the lack of widespread acceptance of Internet access from

the home, as discussed above. Most

transactions are more likely to occur if you are at home or at work and you

want to make a purchase. Going out

to a public venue to shop on-line is not a common practice because you could

just go shopping and come home with the product in-hand since you are already

out and about. Although, the

younger generations are using the Internet more than anyone, which is resulting

in a greater demand for Internet purchased goods (Monge & Cespedes

196).

B2B Electronic Commerce

Over 59% of the

small and medium businesses do not have computers and just about half of those

59% do not consider them necessary to operate their business (Monge &

Cespedes 186). This is a barrier for Costa Rica

because the more businesses that do not embrace technology the harder it will

be to provide online services to Internet users and other businesses. Only 7.9% of the small and medium

businesses use the Internet to sell their products to larger businesses and

12.6% use the Internet to sell their products to small or medium businesses (Monge

& Cespedes 187). More commonly used Internet services,

by small and medium business, in Costa Rica include client services (49.1%) and

shipment monitoring (23.2%) (Monge & Cespedes 187).

Even though the government

has passed bills that allow e-commerce transactions to take place with laws in

place to protect both the consumer and business, businesses are not taking

advantage of the efficiencies in B2B transactions as quickly as other

countries, like the U.S., are doing.

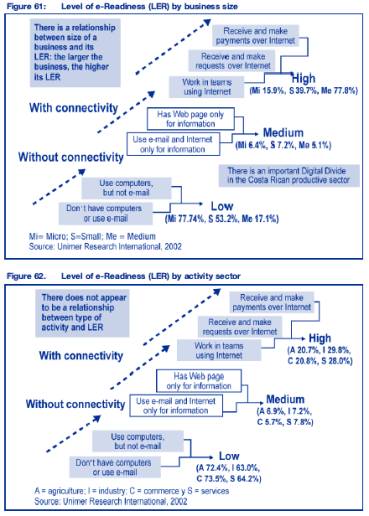

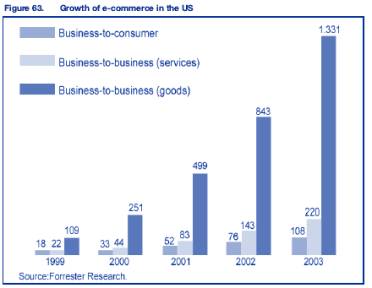

By looking at figure 63 you will see the growth of E-Commerce in the US

over the last 4 years. This is

showing that there are obvious efficiencies gained through B2B business because

of the tremendous growth rate in B2B e-commerce. By looking at figure 61 and figure 62 you will notice that

there is a relationship between the size of the business and the LER (Level of

e-Readiness). “The larger the

business the larger it’s LER.” The

larger businesses are gaining more efficiencies through B2B by incorporating

these technologies into their every-day business practices. With these observations, it is safe to

say that trends seen in the US, in the area of IT, will eventually be seen in

other countries as they catch-up.

In particular, you will notice the exponential growth of B2B business,

which has created tremendous efficiencies for US companies. As the government increases the amount

of B2G (Business-to-Government) Internet transactions, businesses will begin to

see the efficiencies gained.

Overall, the IT trends that US companies are experiencing can also be

experienced in Costa Rica with planning.

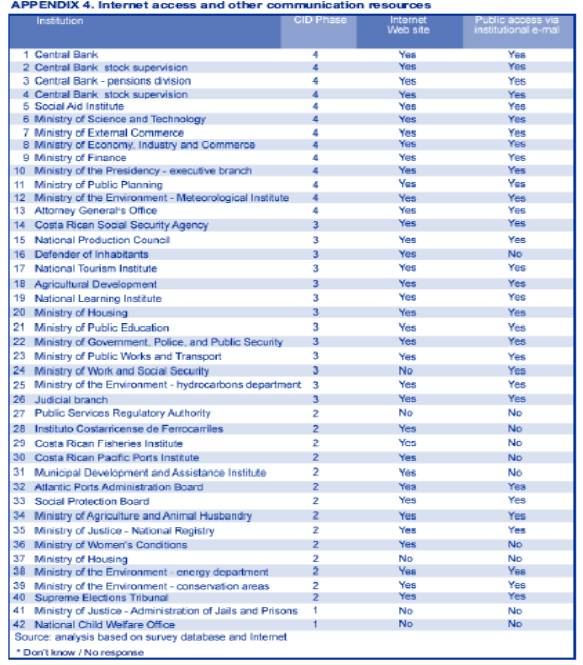

E-Government

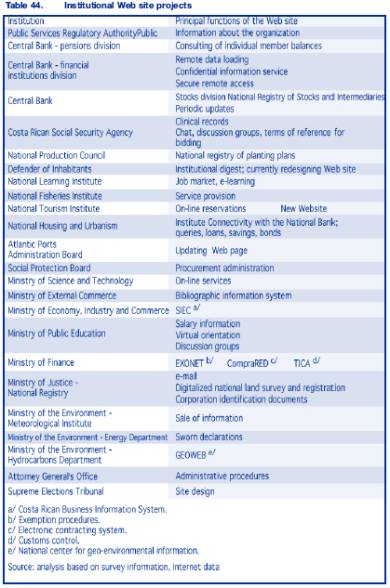

E-Government is considered to be a driving factor in the progression to higher stages of a specific country’s readiness for the networked world. Costa Rica is on its way to improving the services of E-Government as seen in Table 44 and Appendix 4. Table 44 shows the different

institutions with outstanding

web projects, which shows the dedication of some areas of government to provide

streamlined procedures and access to Costa Rican’s. In appendix 4, the results of a recent study indicate that

62% of the institutions fall within a higher level of the matrix because they

take advantage of ICT services that are available to them. Whereas, 38% of the institutions fall

within the lower levels of the matrix and are not taking full advantage of the

technology that is available to them (Monge & Cespedes 159).

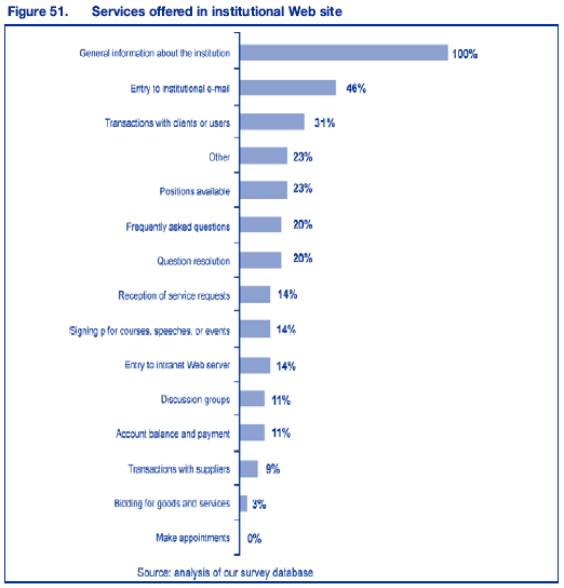

One way to promote E-Government is to offer more access points to the Internet for only governmental services for Costa Rican’s to use along with more interactive government websites to enable ease of doing business. This will allow more of the masses to take advantage of the government procurement, transaction, and distribution systems that are used everyday by businesses and citizens through traditional in-person/paper methods. As you can see in figure 51, 100% of the institutions that have websites provide general information and only 31% of them use the website interactively for transactions like payment of services and on-line consulting (Monge & Cespedes 157). In addition, the Finance Ministry is working on a system to allow tax payments over the Internet (Monge & Cespedes 157).

Home | Network

Access | Networked Learning | Networked Society | Networked Economy | Network Policy | Offshore

Opportunity | Executive Summary | About Costa

Rica | Sources | Authors

| Email

Professor | Back

to IS540