A photo booth is a vending machine or kiosk which contains an automated, usually coin-operated, camera and film processor.

Traditionally photo booths contain a seat or bench designed to seat the one or two patrons being photographed.

Once the payment is made, the photo booth will take a series of photographs (though some modern booths may only take a single photograph and print out a series of identical pictures).

Before each photograph is taken, there will be an indication, such as a light or a buzzer, that will signal the patron to prepare their pose. After the last photograph in the series (typically between 3 and 8) has been taken, the photo booth begins developing the film, which takes several minutes, and delivers a strip of prints.

Both black and white and color photo booths are common. Some modern photo booths use video or digital cameras instead of film cameras, and are under computer control.

Some variants produce stickers, postcards, or other items with the photographs on them, rather than simply a strip of pictures. These often include an option of novelty borders around the photos.

Photo booths are typically installed indoors in places for entertainment, such as arcades and amusement parks. In some cities photo booths may also be found in train stations and other transportation hubs, as a means of obtaining a photograph needed for inclusion in a transit pass.

Origins

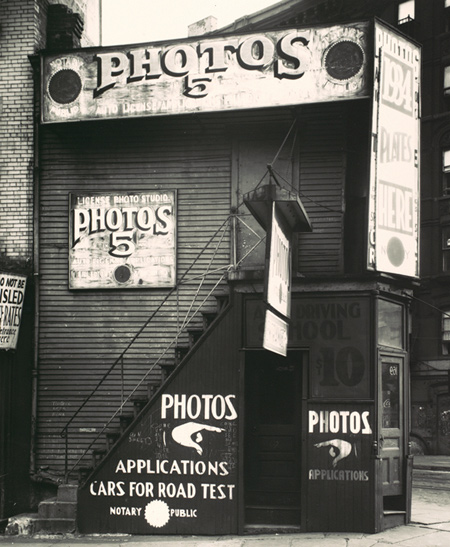

License Photo

Studio, New York, 1934

Walker Evans

The modern concept of photo booth with a curtain, screen or other material covering the background and entrance originated with Anatol Josepho in 1925 with the first photo booth appearing on Broadway Street in New York City.

Josepho had an idea for a small curtain-enclosed booth where people could take affordable portraits anonymously and and automatically. Within 20 years there were more than 30,000 in the US alone, an explosive growth due largely to World War II, as soldiers and loved ones exchanged photos, hoping to cling to memories or moments in a world suddenly turned upside down.

By the 1960's, the Polaroid camera spelled the doom of the "four strip" that had become a fixture at arcades and drugstores everywhere.

Photo sticker machines

Photo sticker machines or photo sticker booths are a special type of photo booth that produces stickers with photos on them. They became very popular in Japan in the 1990s and then spread throughout East Asia, to South Korea and Taiwan. Some have also begun appearing in the United States.

Typically, photo sticker machines produce 4x4 sheets of photo stickers, for a total of 16 photo stickers.

Sticker photos developed in the Japan and have spread to East Asia and some parts of North America. Multiple booths are usually stationed in a store with a counter for money exchange as the booths only accept certain coins and tables with scissors chained to the table for cutting and splitting the photo stickers when finished. There are many variants of sticker photo booths, with the newest ones involving air holes that create a blown hair effect, self changeable backdrops, steps so people can appear to be sitting on hot dogs or other items, and screens outside the booth where users can add on signatures, pictures, clip art and change the lighting or back drop. Sticker photos are popular among students. Group of friends and couples commonly take the photo together in various levels of intimacy and flamboyancy. Some sticker photo booths also allow other users to rate the popularity of previous sticker photos.

Photo booths are no more flexible, allowing users to choose between a variety of combinations of sizes and numbers. This facilitates the splitting between friends. There is also a variant that involves cards, but are more popular between smaller groups of people as only two cards are printed.

Robert Johnson photobooth controversy

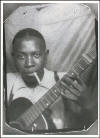

Legendary blues pioneer Robert Johnson left behind very little physical evidence of his existence when he died in 1938. In addition to the 29 songs he recorded, two known photographs of him exist. One, a portrait of Johnson wearing a hat and holding his guitar, was taken at the Hooks Brothers Studio in Memphis in 1938. The other, discovered by Johnson biographer Steven LaVere in a cedar chest belonging to Johnson’s half-sister Carrie Thompson, is a photo booth portrait.

Today, the photos are at the center of a legal quagmire that involves Thompson’s heirs, LaVere (to whom Thompson ceded rights of the photos), a man claiming to be Johnson’s son (who has been named sole heir of his estate) and the CBS label, which produced the blockbuster box set of Johnson’s recordings in 1990. Thompson’s heirs have filed suit against LaVere, Johnson’s sole heir Claud Johnson, and Sony Corporation, which bought CBS Records.

Is this the first time a photobooth photo has been at the center of a legal dispute? The case not only involves the photo itself, but gets at the mechanics of 1930s photobooth technology:

As one of two extant photos of Johnson, the image has been widely distributed and interpreted, and in 1994, became the first photobooth portrait to be turned into a US postage stamp.

The cigarette that dangles from Johnson’s lips was famously removed at the order of the USPS, an interesting change that is analyzed in great detail in Patricia Schroeder’s excellent 2004 work Robert Johnson, Mythmaking, and Contempory American Culture. In order to accommodate the dimensions of the stamp, Johnson’s guitar and hand are also moved slightly, and the drapery background of the original portrait becomes a wall of shingles in stamp designer Julian Allen’s version.

Still waiting to hear the court’s decision in the case, and see who ends up with what may be the most valuable photobooth photo of all time.

Illinois Locations

http://www.photobooth.net/index.php

A film where the photo booth acts as a catalyst to

the central action of the story, Amélie was a critical and commercial

success from the co-director of Delicatessen and The City of Lost

Children, Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Amélie (Audrey Tautou), a shy waitress living

in Paris, dedicates her life to making an impact in the lives of others. Not

nearly as corny as it sounds, the film is beautifully shot, breathtakingly

clever, and very enjoyable.

Amélie first encounters Nino (Matthieu Kassovitz) as he collects scraps of

unwanted photographs from underneath a photo booth in the Abesses metro station

in Paris. As their paths continue to intertwine, Amélie comes across an album he

has made in which he reassembles the ripped photos and comments on their

subjects. She soons begins sending him messages in the form of photo booth

pictures, enticing him to come forward to retrieve his lost album. The numerous

photo booths used in the film were located in the Metro and rail stations of

Paris.

![]() Amélie (Audrey Tautou) and Raymond (Serge Merlin) peruse the album of

re-assembled photos Amelie has found.

Amélie (Audrey Tautou) and Raymond (Serge Merlin) peruse the album of

re-assembled photos Amelie has found.

![]() Amélie poses for a photo in

her Zorro costume.

Amélie poses for a photo in

her Zorro costume.

![]() Amélie peers out of a photo

booth.

Amélie peers out of a photo

booth.

![]() Nino (Matthieu Kassovitz) looks around a

photo booth hoping to find out where his lost album might be.

Nino (Matthieu Kassovitz) looks around a

photo booth hoping to find out where his lost album might be.

![]() The man (Ticky Holgado) in Amélie's

photobooth picture note speaks to Nino about Amélie as he falls asleep.

The man (Ticky Holgado) in Amélie's

photobooth picture note speaks to Nino about Amélie as he falls asleep.

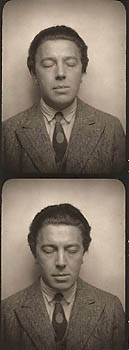

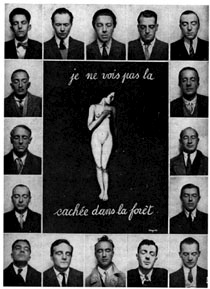

Andre

Breton

Andre

Breton

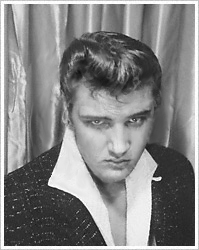

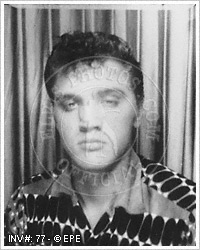

Elvis

Elvis

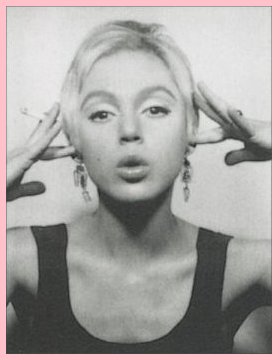

Edie Sedgwick

Edie Sedgwick