Depth of Field

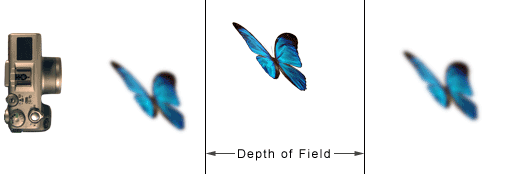

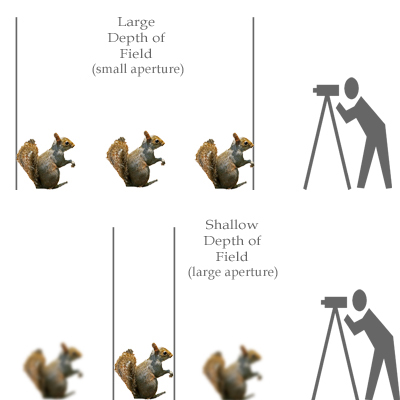

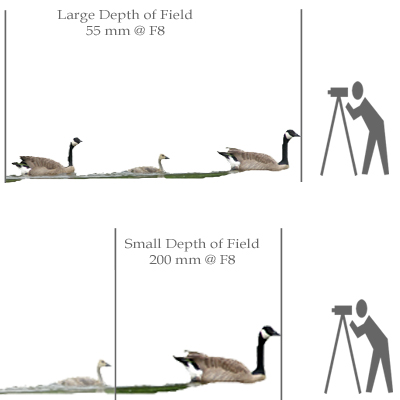

Depth of field is the amount of distance between the nearest and farthest objects that appear in acceptably sharp focus in a photograph.

A large depth of field means that a large area both in front and behind your main subject will appear sharp. A shallow depth of field implies that anything other than your main focus point will appear blurred. A smaller f-stop (F2) will create a shallow depth of field. A larger f-stop (F11) will create a greater depth of field.

A preferred selection Depth of field ("DOF") in a focused subject in an image can be quite subjective. Remember this, adequate selection of DOF for one situation, application may be unacceptable for another photographer. It is all a matter of personal preference when trying to determine the appropriate use of DOF to enhance an effect in a photograph.

When altering the aperture, the shutter speed also needs to be taken into consideration. A larger amount of light entering the camera necessitates a shorter shutter speed and a small opening requires a longer shutter speed for the same amount of light.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Quick Reference Guide: Depth of field is governed by three factors: aperture, lens focal length and shooting distance. Remember the following relationships:

Another characteristic of depth of field is that it is generally deeper in the background than in the foreground.

Bokeh

Although difficult to quantify, some lenses enhance overall image quality by producing more subjectively pleasing out-of-focus areas, referred to as bokeh. Bokeh is especially important for large-aperture lenses, macro lenses, and long telephoto lenses because they are typically used with a shallow depth of field. Bokeh is also important for "portrait lenses" (typically medium telephoto — 85–150 mm on 35-mm format) because the photographer would typically select a shallow depth of field (wide aperture) to achieve an out of focus background and make the subject stand out.

Bokeh characteristics may be quantified by examining the image's circle of confusion. In out-of-focus areas, each point of light becomes a disc. Depending how a lens is corrected for spherical aberration, the disc may be uniformly illuminated, brighter near the edge, or brighter near the center. Lenses that are poorly corrected for spherical aberration will show one kind of disc for out-of-focus points in front of the plane of focus, and a different kind for points behind. This may actually be desirable, as blur circles that are dimmer near the edges produce less-defined shapes which blend smoothly with the surrounding image. Lens manufacturers including Nikon, Canon, and Minolta make lenses designed with specific controls to change the rendering of the out-of-focus areas.

The shape of the aperture has a great influence on the subjective quality of bokeh. When a lens is stopped down to something other than its maximum aperture size (minimum f-number), out-of-focus points are blurred into the polygonal shape of the aperture rather than perfect circles. This is most apparent when a lens produces undesirable, hard-edged bokeh, therefore some lenses have aperture blades with curved edges to make the aperture more closely approximate a circle rather than a polygon. Lens designers can also increase the number of blades to achieve the same effect. Canon's EF 85mm f/1.2L II lens (often used for portraits) is an example of an almost circular aperture diaphragm.

Leica (formerly Leitz, "Leica" only referring to the camera body until more recently) lenses, especially vintage ones, are often claimed to excel in this respect, although Leica photographers have tended to make more use of maximum aperture due to the lenses' ability to maintain good sharpness at wide openings and the suitability of the Leica camera system for available-light theatre work and reportage. Consequently, more evidence is needed to determine whether Leica's lens designers deliberately set out to produce pleasing bokeh.