Cave Painting of a Bison, Altamira,

Spain c. 15,000-10,000 B.C.E.

Cave Painting of a Bison, Altamira,

Spain c. 15,000-10,000 B.C.E.Frames and Screens

Why Frame a Picture?

1. To separate inside from outside; to state that a picture is a world of its own, and not a part of the surrounding world.

2. To provide visual control. This separation from the outside world makes it possible for the painter to control the composition. The meaning of things we see depend partly on their surroundings, so if the surroundings can't be controlled, the meanings cannot be controlled either.

3. For portability

No Frame: Prehistoric Wall Paintings.

Cave Painting of a Bison, Altamira,

Spain c. 15,000-10,000 B.C.E.

Cave Painting of a Bison, Altamira,

Spain c. 15,000-10,000 B.C.E.

Of course, not all pictures were framed. Cave paintings are an example of unframed pictures which generally focus on a single figure or animal, without much regard to the surrounding figures.

Rectangular Format

what shape to use? The shape of a frame is often called the format.

Historically, as artists turned from painting on wood panel to canvas, the use of the rectangular format increased because it is easier to cut wood into interesting shapes than to construct frames in these shapes and stretch canvas over them.

Portrait or Landscape

Once we have decided to use a rectangle, we must decide on (1) orientation and (2) proportions of that rectangle.

By orientation, we simply mean whether the long side of the rectangle is vertical or horizontal. Of course, a landscape normally calls for a horizontal format; a portrait calls for a vertical format. Computers even use the terms portrait and landscape to distinguish between the vertical and horizontal formats.

The orientation may affect how the contents are seen. For example a standing figure painted in a portrait format appears taller and thinner; a standing figure painted in a landscape format is accentuated. It stands out more, because of the contrast with the horizontal frame.

What Shape Rectangle?

So once you decided whether to orient it portrait or landscape, what proportions do you make it?

Within the rectangular format, there's one format for movie films, another format for wide-screen movies, and for video, others for different kinds of photographic film, and still others for paper, like the 8.5 x 11 format.

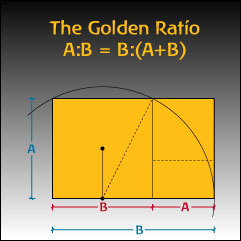

Golden Rectangle

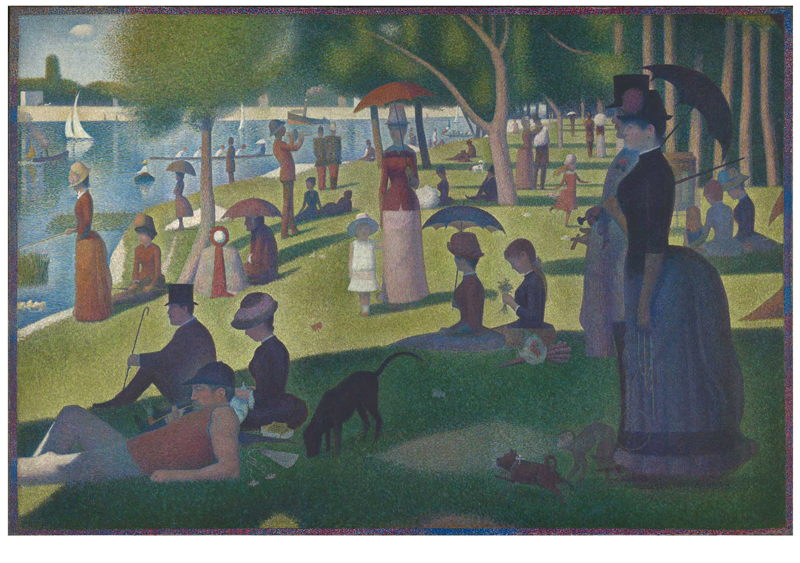

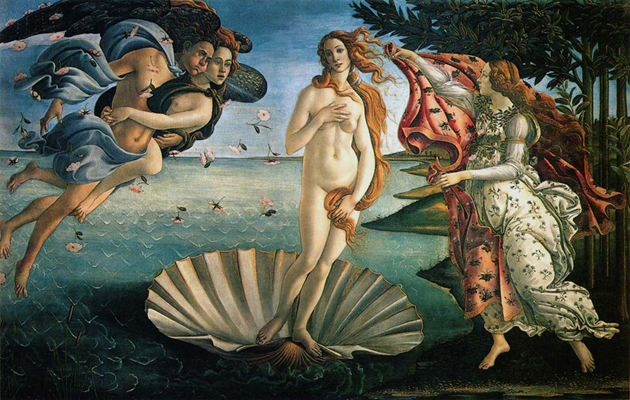

Slide 10-38: Botticelli, Birth of Venus

Why not use the golden section for every painting,

as it is often claimed to be the most esthetically pleasing. The

Golden Section is also known as the Golden Mean, Golden Ratio and Divine

Proportion. It is a ratio or proportion defined by the number Phi

(Φ

=

1.618033988749895...)

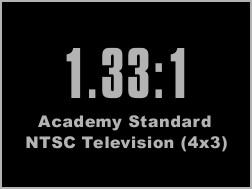

Aspect ratio is the fractional relation of the width of a video image compared to its height. The two most common aspect ratios in home video are 4:3 (also known as 4x3, 1.33:1, or standard) and 16:9 (16x9, 1.78:1, or wide-screen). All the older TVs and old computer monitors have the squarish 4:3 shape--only 33 percent wider than it was high.

On the other hand, 16:9 is the native

aspect ratio of most HDTV programming; it is 78 percent wider than it is tall,

or fully one-third wider than 4:3.

At comparable screen sizes, the wide-screen image is a distinct improvement: it

offers a larger image, and the horizontal orientation is more akin to how your

eyes view objects.

Both of these formats work perfectly well when they match the TV screen's native

aspect ratio--standard programming on a 4:3 screen (any 1950s to 1990s Nick at

Nite fare, for instance) and any newer, wide-screen material on a 16:9 set (HDTV

programming or most DVDs).

In still camera photography, the most common aspect ratios are 4:3 and 3:2, though other aspect ratios, such as 5:4, 7:5, and 1:1 (square format), are used.

|

Five common aspect ratios |

|

|

72x54 |

|

|

81x54 |

|

|

96x54 |

|

|

100x54 |

|

|

129x54 |

|

4:3 is the aspect ratio defined by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as a standard after the advent of optical sound-on-film.

By having TV match this aspect ratio, films previously photographed on film could be satisfactorily viewed on TV in the early days of the medium (i.e. the 1940s and the 1950s). When cinema attendance dropped, Hollywood created widescreen aspect ratios in order to differentiate their industry from the TV.

The Way Movies Looked

After the 1950s... and Still Do Today

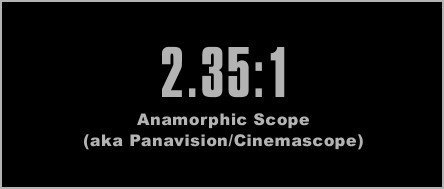

In 1953, 20th Century Fox introduced the world to the CinemaScope, which was used by many studios between 1953 and 1967 (it eventually gave way to Panavision, which is the most used widescreen process today). In 1953, there were some 5 films released in a widescreen aspect ratio. By the following year, there were nearly 40. And by 1955, the number had exploded to more than 100.

Today, widescreen dominates American filmmaking in a variety of aspect ratios. But there are two "standardized" ratios that are by far the most common: Academy Flat (1.85:1) and Anamorphic Scope (2.35:1).

Some of you may remember the old 3D films, which required that you wear a pair of stereoscopic glasses (one of the plastic filters the glasses used for "lenses" was blue and one was red). Experiments with both 3D and widescreen in films had been occurring since the early 1920s, but it was the 50s that they really took off.

http://widescreenmovies.org/WSM11/3D.htm

The red and blue lenses filter the

two projected images

allowing only one image to enter each eye.

House of Wax was an instant hit when it premiered in New York on 10th April 1953, and deservedly so; it is still a hugely entertaining film when seen today, even in a flat version. But at the time, the sumptuous color and superb 3D photography and six-track stereophonic sound were a revelation - the latter all the more remarkable because the director, Andre de Toth, was blind in one eye therefore and had no stereoscopic perception.

It was also presented in a widescreen format of 1.66:1 rather than the usual 1.33:1. It would remain the highest grossing 3D movie until 1969s The Stewardesses - a low-budget sexploitation flick.

IMAX 3D

THE NEXT BIG THING

The Experience begins with the

IMAX® 3D camera

To create the illusion of three-dimensional depth, the IMAX 3D process uses two

camera lenses to represent the left and right eyes. The two lenses are separated

by an interocular distance of about 64 mm/2.5 in., the average distance between

a human's eyes. By recording on two separate rolls of film for the left and

right eyes, and then projecting them simultaneously, we can be tricked into

seeing a 3D image on a 2D screen. The IMAX 3D camera is very cumbersome,

weighing over 113 kg/250 pounds. This makes it extremely difficult to film

on-location documentaries.

In May 2015, it was announced that Marvel Studios's two-part film, Avengers: Infinity War, will be filmed entirely in IMAX, the first Hollywood feature film to do so, using a modified version of Arri's Alexa 65 digital camera.

The IMAX® 3D projector

During projection, the left and right eye images are polarized

perpendicular to one another as they are projected onto the IMAX screen. By

wearing special eyeglasses with lenses polarized in their respective directions

to match the projection, the left eye image can be viewed only by the left eye

since the polarization of the left lens will cancel out that of the right eye

projection, and the right eye image can be viewed only by the right eye since

the polarization of the right lens will cancel out that of the left eye

projection.

The IMAX® screen

The new screen is covered with a special silver paint that reflects twice the

amount of light as a regular movie screen. It has a slight curvature that

extends beyond the field of geometric recognition, incorporating the audience’s

peripheral vision to enhance the feeling of being IN the film.

With the worlds first* introduction of digital interchangeable lens for 3D still photography with an interchangeable lens system camera, Panasonic proposes to enjoy high-quality shooting in 3D with DMC-GH2.

This new compact optional 3D-capable

interchangeable lens allows easier handling and instant 3D shooting. It produces

3D images without distortion or time lag between left and right images, even for

moving objects. The 3D images, even close-up shots, taken with this lens are

easy on the eyes when viewed on 3D VIERA televisions (mpo side by side format).

Panasonic made a breakthrough by adding this special way of unprecedented

expression in photography with outstanding ease with this innovative technology.

Both still images and motion images in AVCHD

recorded on SD Memory Cards are easy to view on a Panasonic VIERA TV with

dynamic HD resolution. The user simply inserts the card into the VIERA Image

Viewer (SD Memory Card slot) on a VIERA TV or DIGA Blu-ray Disc Player* to play

the content. Alternatively, an optional HDMI mini cable can be used to output

still and motion images recorded with the DMC-GH2 directly to the TV for easy

VIERA Link operation. This makes it possible to take maximum advantage of the

camera's playback functions, including slideshows in which both still and motion

images are played sequentially, or calendar displays and so on. All control is

possible using only the TV's remote control. Especially, the pictures taken with

the interchangeable 3D lens LUMIX G 12.5mm / F12 can be viewed in 3D via the 3D

Image Viewer offering users a whole new exciting experience.

In addition, with the included software PHOTOfunSTUDIO 6.0 BD Edition, it is

easy to view and edit your recorded contents. You may also choose to upload your

videos to YouTube or burn them onto a Blu-ray or DVD disc for archiving.